Morbid Curiosity and Death Avoidance: A San Diego Death Doula’s Perspective

Why So Many of Us Are Drawn to Morbid Subjects

Why are so many of us drawn to morbid subjects like true crime, violence, and stories of death, yet so resistant to thinking about our own mortality?

That question has been sitting with me for a while.

As a death doula and end-of-life planner based in San Diego, I spend my time helping people talk about illness, aging, dying, and what comes at the end of life. At the same time, I watch friends, clients, and even myself regularly consume content that revolves around death in a very different way. True crime podcasts. Violent documentaries. Stories of tragedy, disasters, and loss.

What continues to puzzle me is the contrast. Many people are deeply interested in death as a subject, yet profoundly uncomfortable when it comes to acknowledging their own mortality or doing any kind of advance planning. We will listen to hours of stories about someone else’s worst day, but avoid a single conversation about what would happen if that day were ours.

Recently, that question sharpened for me when I listened to an episode of Armchair Expert featuring psychologist Coltan Scrivner. Hearing him speak felt like a thread I had been tugging on suddenly came into focus.

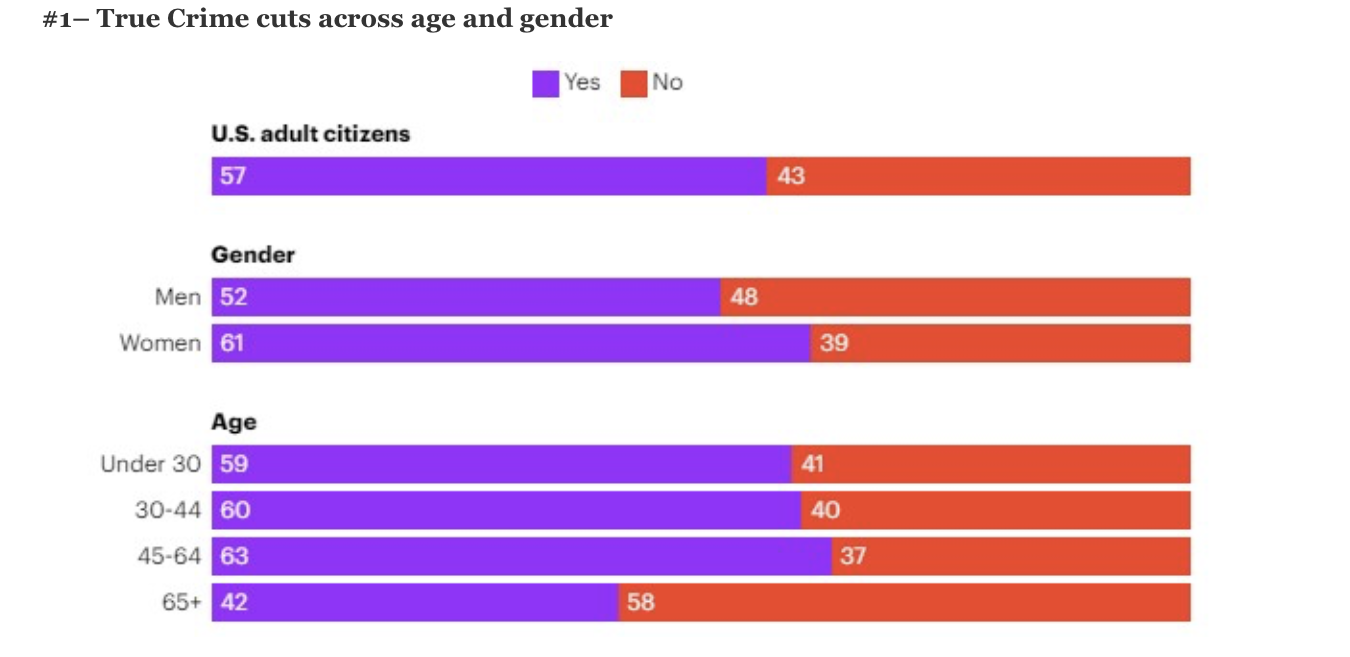

This chart shows true crime consumption across U.S. adults by gender and age. Women report higher engagement than men, and interest remains strong across most age groups, peaking among adults ages 45–64.

Who Is Coltan Scrivner and What Is Morbid Curiosity

Coltan Scrivner is a behavioral scientist and psychologist whose research focuses on morbid curiosity. That is our attraction to dark, threatening, or taboo information. His work explores why humans are drawn to true crime, horror, violence, disasters, and stories of death, even when those topics are disturbing or uncomfortable.

Rather than viewing morbid curiosity as unhealthy, his research frames it as a meaningful psychological response. Morbid curiosity can be understood as an interest in information related to potential threats to survival, whether real or fictional, immediate or distant.

When we listen to a true crime podcast or watch a documentary about a tragedy, we are engaging with danger from a place of relative safety. We are able to observe, analyze, and emotionally react without being personally at risk. There is increasing evidence that this kind of engagement allows the brain to simulate threat, process fear, and learn from danger without direct exposure.

In that sense, morbid curiosity is not just entertainment. It may be a way humans try to understand how bad things happen, how harm unfolds, and how we might protect ourselves and others.

And yet, this is where a contradiction appears.

Why Distance Matters When We Think About Death

If we are willing to engage deeply with stories of death and danger when they are at a distance, why do so many of us shut down when asked to think about our own dying, our own medical wishes, or what would happen to our loved ones if we could not speak for ourselves?

The more I sit with this, the more it feels like a matter of psychological distance.

True crime allows us to look at death sideways. It belongs to someone else. It happened somewhere else. There is a buffer between the story and our own lives. We can pause the episode, turn it off, or remind ourselves that this is not us.

Our own death does not offer that distance.

Thinking about our personal end of life collapses the space between observer and subject. There is no narrator and no frame that says this is just information. It is us in the hospital bed, our partner being asked to make decisions, or our children trying to interpret what we would have wanted with no guidance.

For many people, that shift from curiosity to intimacy is where avoidance takes over.

The Cultural Disconnect Between Death as Entertainment and Death as Reality

We live in a culture where death is everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

Violence, tragedy, and disaster are packaged as content. They are consumed freely and discussed openly. But real death, personal death, and dying are rarely treated as something worthy of advance conversation or preparation.

We talk freely about crimes and autopsies, yet struggle to talk about advance directives. We know the details of strangers’ final moments, but not the wishes of the people closest to us.

In my work as a San Diego death doula, I meet people who are thoughtful, responsible, and deeply caring. These are people who plan carefully for careers, parenting, travel, and finances. When it comes to end-of-life planning, they often freeze.

This resistance does not usually come from ignorance. Most people understand that death is inevitable. The barrier is emotional. It is less about not knowing what to do and more about what it feels like to imagine doing it.

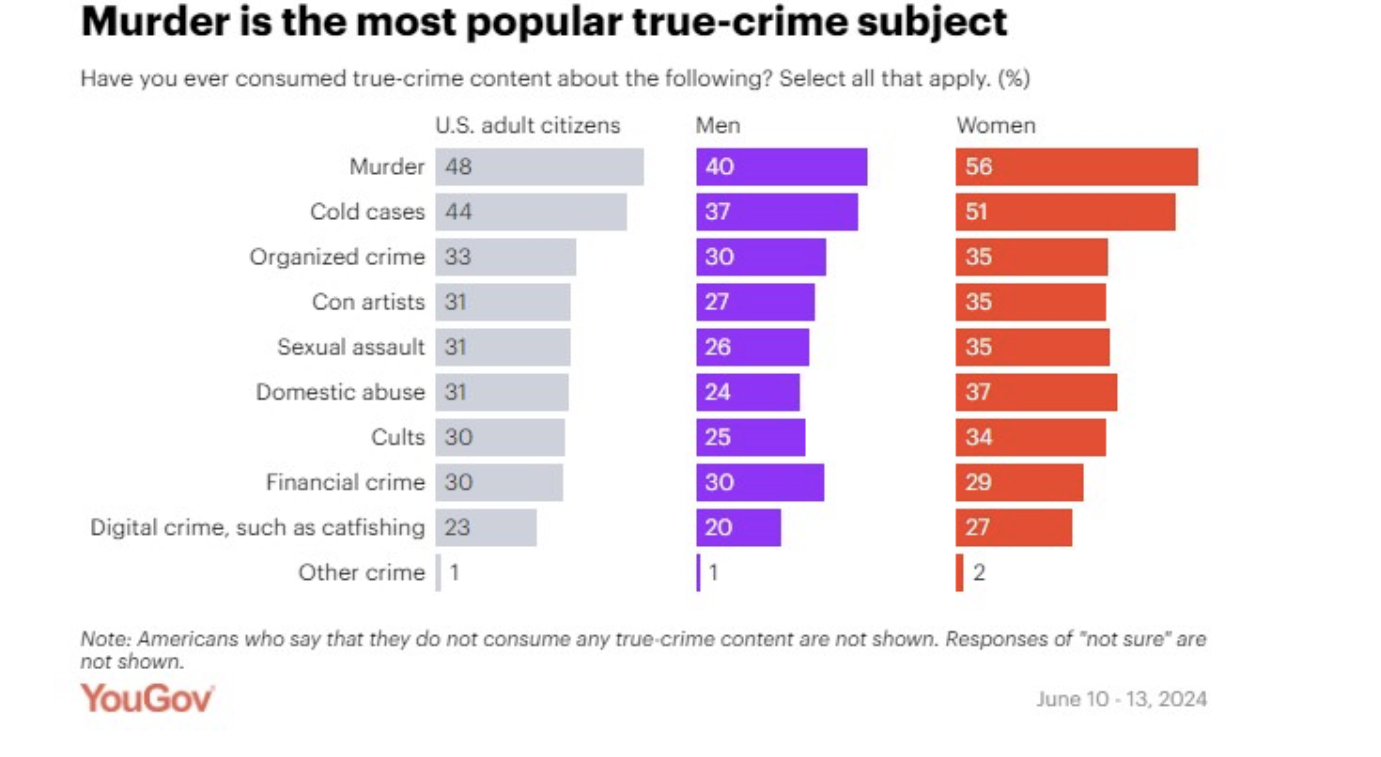

This chart shows the types of true crime content consumed by U.S. adults. Murder is the most commonly consumed subject overall, followed by cold cases. Women report higher engagement than men across most true crime categories.

Why Avoidance Is Emotional, Not Intellectual

End-of-life planning does not fail because people do not understand its importance. It stalls because of fear, vulnerability, and the discomfort of imagining loss.

Planning requires us to acknowledge uncertainty. It asks us to consider moments we cannot fully control and to picture our loved ones without us. For many people, that emotional weight is heavier than the practical tasks themselves.

This is why even highly capable, organized people delay these conversations. Avoidance is not a moral failure or a lack of responsibility. It is a deeply human response.

Why Morbid Curiosity May Be a Doorway, Not a Problem

This is where morbid curiosity becomes interesting to me.

If so many people already engage willingly with death-related stories, it tells us something important. People are not incapable of thinking about death. What they struggle with is personal proximity, vulnerability, and loss of control.

Morbid curiosity allows engagement without exposure. End-of-life planning asks for exposure first. But planning also offers something morbid content does not. It offers agency.

End-of-life planning allows us to shape the experience for the people we love, even when circumstances are uncertain. It creates clarity in moments that are often chaotic and painful.

Instead of seeing morbid curiosity and end-of-life planning as opposites, I wonder what could happen if we viewed them as connected.

What If We Redirected Even a Small Percentage

True crime is one of the most consumed genres across podcasts, streaming platforms, and documentaries. End-of-life planning, by contrast, remains something most Americans delay or avoid.

If even a small percentage of people already immersed in stories of death and danger felt supported in facing their own mortality with curiosity instead of fear, the impact could be meaningful.

Families would experience less confusion. Caregivers would carry less emotional burden. Loved ones would have clearer guidance during some of the hardest moments of their lives.

This is not about forcing people to confront death before they are ready. It is about recognizing that many people are already halfway there. They just do not realize it yet.

An Invitation to Approach Planning Differently

If you are someone who loves true crime, documentaries, or stories that explore the darker edges of life, and you have not done much end-of-life planning, you are not failing. You are human.

Morbid curiosity shows that part of you is already willing to look at difficult truths. End-of-life planning simply asks that you turn a small portion of that attention toward yourself and the people you love.

If that feels like a conversation you want to have thoughtfully and at your own pace, that is the work I do through The Everafter Collective.

Curious, but not sure where to start?

End-of-life planning does not have to be overwhelming. It can be thoughtful, values-based, and deeply human.

As a San Diego death doula and end-of-life planner, I support individuals and families who want to think ahead without fear or urgency. Whether you are just beginning to ask questions or ready to put plans into place, you do not have to do it alone.